Author: Marta Kozak-Maśnicka

Long awaited legislation finally arrives

Poland is the last of the 27 EU Member States to adopt whistleblowing legislation to transpose the EU Directive on Whistleblowing. On 14th June this year, almost 2 and a half years since the official deadline for full transposition, the Act on the Protection of Whistleblowers was adopted by Parliament. The new law will enter into force on 25 September with some provisions for external reporting due to enter into force later, on 25 December 2024.

The Act adoption follows an intense legislation battle which lasted two and a half years and despite the Bills very long preparation time, the final law is not fine-tuned, creating several causes key areas for concern.

Read more: Poland’s Whistleblowing Law: A Chaotic Journey to Compliance’ (Blog – EWI)

Such delays resulted in the EU Commission making a referral to the European Court of Justice, which subsequently imposed financial penalties on Poland including a lump sum of €7 million and a daily fine of €40,000 until compliance is achieved.

Unprotected workers: Labour law loophole

Firstly, labour law breaches have been excluded from the material scope of the Act – that is, the types of wrongdoing which can be reported. Employer representatives who lobbied for this change argued that violations of labour law should be reported to the Polish Labour State Inspectorate and that whistleblowing law should concern public interest, not personal matters. Exclusion breaches of labour law from the scope of the Act were intended to protect entities from a flood of reports regarding insignificant matters. However, this amendment may leave persons reporting serious violations like breaches of health and safety rules unprotected.

Identity protection safeguards compromised

Secondly, the legislator does not take sufficient care of the protection of whistleblowers' identity - one of the key mechanisms guaranteeing protection of reporting persons against reprisals. The Act does not defer the obligation to fulfil Article 14 GDPR according to which a data controller has to provide a data subject with the information about processing of his or her personal data in connection with a whistleblowing report. Consequently, the person concerned in the report may try to influence proceedings following the report and potentially obtain information allowing them to guess who a whistleblower is, which raises the risk of retaliation. Furthermore, reporting persons must provide a contact address for effective follow-up and feedback. This likely means that, anonymous reports (which are allowed by the Act) may remain unaddressed.

Whose responsible? Ambiguous public authority duties

Thirdly, there is no list of the public institutions obligated to establish external reporting procedures and follow-up on reports. The definition of a public authority that should implement external whistleblowing procedures is vague. Therefore, potentially none of the public authorities will feel competent to receive reports. Even an ombudsman, who can receive and forward external reports to the authorities responsible for the type of wrongdoing reported, may not be considered qualified to resolve competence disputes.

Deterrent deficit: Penalties too lenient

Finally, one of the main disadvantages of the Act is that no effectively dissuasive penalties for legal entities for failing to implement reporting channels have been included. A fine for those responsible for establishing an internal procedure (e.g. members of the board of directors) is insufficient to ensure that whistleblowing mechanisms are effectively implemented in all entities with more than 50 workers.

Progressive element? Exceeding minimums

On a more positive note, the Act established higher standards than the minimum standards of the Directive e.g. by deciding to covering a wide scope of persons that can report violations. Moreover, the Ombudsman may play a crucial role in providing information and advice for whistleblowers and other persons concerned.

Conclusion – much to review

While the new whistleblowing law marks progress in protecting whistleblowers in Poland, significant improvements are still needed to ensure comprehensive protection and effective implementation. As the law will be reviewed in two years, there is a vital opportunity for stakeholders to address these shortcomings and enhance the effectiveness of Poland's whistleblowing framework. Only through continued refinement and commitment to robust protections can Poland achieve full compliance with the EU Directive and create a safer environment for those who expose wrongdoing.

Marta Kozak-Maśnicka is a polish Lawyer, country editor for Poland the EU Whistleblowing Monitor, a PhD candidate at the University of Warsaw and also a fellow at the European Whistleblowing Institute.

Written by Ida Nowers, EU Whistleblowing Monitor Law and Advocacy Manager

Introduction

Just a few weeks after the final EU country adopted a new whistleblowing law to transpose the EU Directive on Whistleblowing, the European Commission has issued its report on its implementation and application.

The eleven-page report, published on 3 July 2024, reviews the transposition efforts of 24 of the 27 Member States and highlights several areas where many of the new laws do not meet the Directive’s requirements, the purpose of which was to harmonise a minimum standard of protection across the Union.

The Directive required Member States to implement provisions including mandatory confidential reporting channels in organisations and competent authorities, provision of full compensation for retaliation and access to advice and support, as well as effective dissuasive penalties. It has been described as 'groundbreaking' in moving forward evolving standards for whistleblower protection laws.

However, the approach of Member States to the transposition has been described as delayed, confused, and minimal. The 27 countries had two years until 21 December 2021 to transpose the new requirements; however, only three completed efforts to transpose on or before this date. Several countries were referred to the European Court of Justice for severe delays, and significant fines have already been ordered.

Read: Judgement of the CJEU in the case of EU Com v Poland

Worryingly, recent analysis from civil society found that many of the transposition laws do not meet the requirements of the Directive or international best practice principles.

Read more: How well do EU countries Protect Whistleblowers: Assessing the transposition of the EU Whistleblower Protection Directive (Report - Transparency International) and Beyond Paper Rights: Implementing Whistleblower Protections in Central and Eastern Europe (Report – CEELI)

Further, there are now several initiatives by civil society organizations attempting to formally raise concerns for non-compliance of respective laws through letters to the Commission and infringement complaints.

Read More: Complaint to the European Commission against Germany (Whistleblower-Netzwerk e.V) and Blowing the whistle to protect whistleblowers in Europe (Blog – Transparency International)

Summary of report findings

The report, which concludes an assessment of the national measures, confirms these concerns, highlighting several instances where member states' transposition does not comply with the requirements of the Directive. For example, some member states have:

- Restrictively implemented the material scope (types of wrongdoing that can be reported) to exclude certain breaches or narrowly interpreted key standards such as ‘reasonable suspicions.’

- Restrictively transposed the personal scope, which should protect a wide range of individuals, to omit categories such as volunteers, contractors, or suppliers.

- Incorrectly included consideration of the whistleblowers' motives for reporting as a condition for protection.

- Imposed conditions that limit the freedom to report directly to external authorities or make public disclosures under specific circumstances not included in the Directive.

- Incorrectly allowed larger employer entities to bypass the requirement to establish internal reporting channels by allowing for group-level arrangements or imposed limitations on external reporting such as excluding reports committed more than two years prior to reporting.

- Improperly transposed the duty of confidentiality, omitting key safeguards to protect the whistleblower's identity.

- Omitted to prohibit any form of retaliation.

- Not guaranteed access to independent information, advice, and legal aid by not providing for individual advice or effective assistance.

- Inadequately transposed remedial measures (such as the reversed burden of proof and interim relief measures) leading to legal uncertainty.

Conclusion

This new report highlights various discrepancies and incomplete transpositions among Member States, underscoring the need for ongoing efforts to achieve full and consistent implementation. Presumably, the European Commission will continue to monitor the implementation of the Directive, taking steps to ensure that all Member States fully comply with its provisions. Infringement proceedings will continue or begin where necessary. The Commission already seems ready to impose financial sanctions to incentivize timely and accurate transposition.

The EU Whistleblowing Monitor – and its team of voluntary country editors – will continue to track developments in the implementation of the Directive, providing a source of information and resources for the public, policymakers, and advocates to continue to hold EU governments accountable for the proper protection of whistleblowers. This ensures they can speak up to stop harm and protect the public interest for all.

Visit today: EU Whistleblowing Monitor

This Article was first published on 23 June 2024 by Transparency International on World Whistleblowers Day.

In October 2019, after years of campaigning by civil society, the European Union (EU) passed a directive requiring member states to put in place strong legal protections for whistleblowers. No longer would people reporting tax fraud, environmental damage, or other breaches of European law have to hope that national legislation protected them if they faced retaliation from their employers.

After a slow start, all but one EU country has finally implemented the Whistleblowing Directive (EU Directive 1937/2019) into national laws. Poland, which was recently fined €7 million by the European Court of Justice for not doing so, should join the rest shortly: the country faces an additional penalty of €40,000 per day until it implements the Directive. Yet there is still considerable room for other European countries to continue strengthening whistleblower protection. Legislation in the 20 countries we assessed last year falls short in crucial areas.

In some countries, the national laws are problematic enough that Transparency International has turned “whistleblower” itself, alerting the European Commission to issues with how member states have implemented the Directive.

The first of these occurred in Hungary last year. In a move that seems destined to sow confusion, the Hungarian government has created two parallel systems: an old system that covers whistleblowers reporting breaches of Hungarian national law, and a new one that implements the Directive and only covers whistleblowers who report breaches of EU law.

Miklos Ligeti, the Legal Director of Transparency International Hungary, said: “It’s a mess. It takes a lawyer to define which case belongs in which system. It can be a Hungarian case with weaker protection, or an EU case covering narrower issues but with better protections. It is intimidating, dissuasive and a deterrent to Hungarians. Whistleblowing should be easy.”

The newly adopted piece of legislation law also leaves whistleblowers who speak to the media unprotected. In an environment where public sector corruption is on the rise, government employees in particular might feel that they need to alert the press in order to raise the alarm. “When the constellation of corruption in Hungary is so sobering,” says Ligeti, “you need to be able to speak freely. That is not an option.”

In a letter to the European Commission, Transparency International’s chapter in Hungary and another local anti-corruption nonprofit K-Monitor have expressed their concerns that excluding whistleblowers who report to the media “clearly violates the Whistleblowing Directive,” and therefore “seriously endangers the European Union as an area of freedom, security and justice.”

Part of the problem, says Ligeti, is that the Whistleblowing Directive has been low on the government’s agenda. Whereas the Directive envisages national campaigns explaining and promoting the new rules, in Hungary this has not happened. As in many contexts, “being a whistleblower can be a very painful experience in Hungary, because there is no broad consensus that reporting on any form of wrongdoing serves the public good. Blowing the whistle is regarded as an individual and solitary action. The sentiment is: if you’re in trouble, you’re on your own,” Ligeti continues.

The Hungarian government has recently clashed with the European Commission over corruption and rule of law in the country, and, in this case too, Ligeti believes, further engagement from Brussels is likely to be helpful. In 2025, many municipalities and medium sized enterprises will have to implement their internal reporting systems as part of the Directive transposition. This creates the perfect opportunity to smooth out the issues and create a single clear and comprehensive framework to protect Hungarians. Pressure from the Commission might help create the necessary impetus, Ligeti explains.

In Italy, meanwhile, Transparency International has raised the alarm that the new whistleblower protection legislation is actually a step backwards in some important respects.

In 2017, Italy’s parliament passed a law that protects whistleblowers who first raise their concerns outside their organisations. But, transposing the Directive, the government has put limits on when whistleblowers can report externally and still be protected. While the Directive encourages employees to first raise the alarm within their organisations, it expressly allows them to go directly to the authorities.

Rather than legally requiring whistleblowers to report internally first, the government should use softer incentives, says Giorgio Fraschini, Whistleblowing Program Manager at Transparency International Italy. “When an external authority investigates, it is like an elephant in a crystal shop,” he says. “They don’t know the relationships and the practices of the workplace. Internal reporting is a more controlled system. A better system would promote internal reporting for these reasons, while leaving the choice of where to report to the whistleblower.”

The new Italian law also changed the scope of what can be reported, creating a confusing division between the public and private sectors, and excluding reports of irregularity and maladministration in the public sector. It ignores a key principle of the Directive – that its transposition should not create weaker protection for whistleblowers compared to previous national legislation. As in Hungary, whistleblowers will have a hard time understanding which cases can be reported. The weak consequences of retaliation against whistleblowers are another area of concern.

Many of the issues with the implementation of the Directive in Italy could have been avoided if the government had consulted with civil society, Fraschini says. Although the 2017 law was not perfect, it was drafted with considerable input from civil society experts. While transposing the Directive, the Italian government did not seek any public participation. As a result, it appears to have had problems aligning the Directive from Brussels with the existing national law.

The original article can be read on the Transparency International website here.

For more information on the Strengthening and Fostering of an enabling environment for whistleblowers in the European Union (Safe for Whistleblowers) see here.

Written by Ida Nowers, EU Whistleblowing Monitor Law and Advocacy Manager

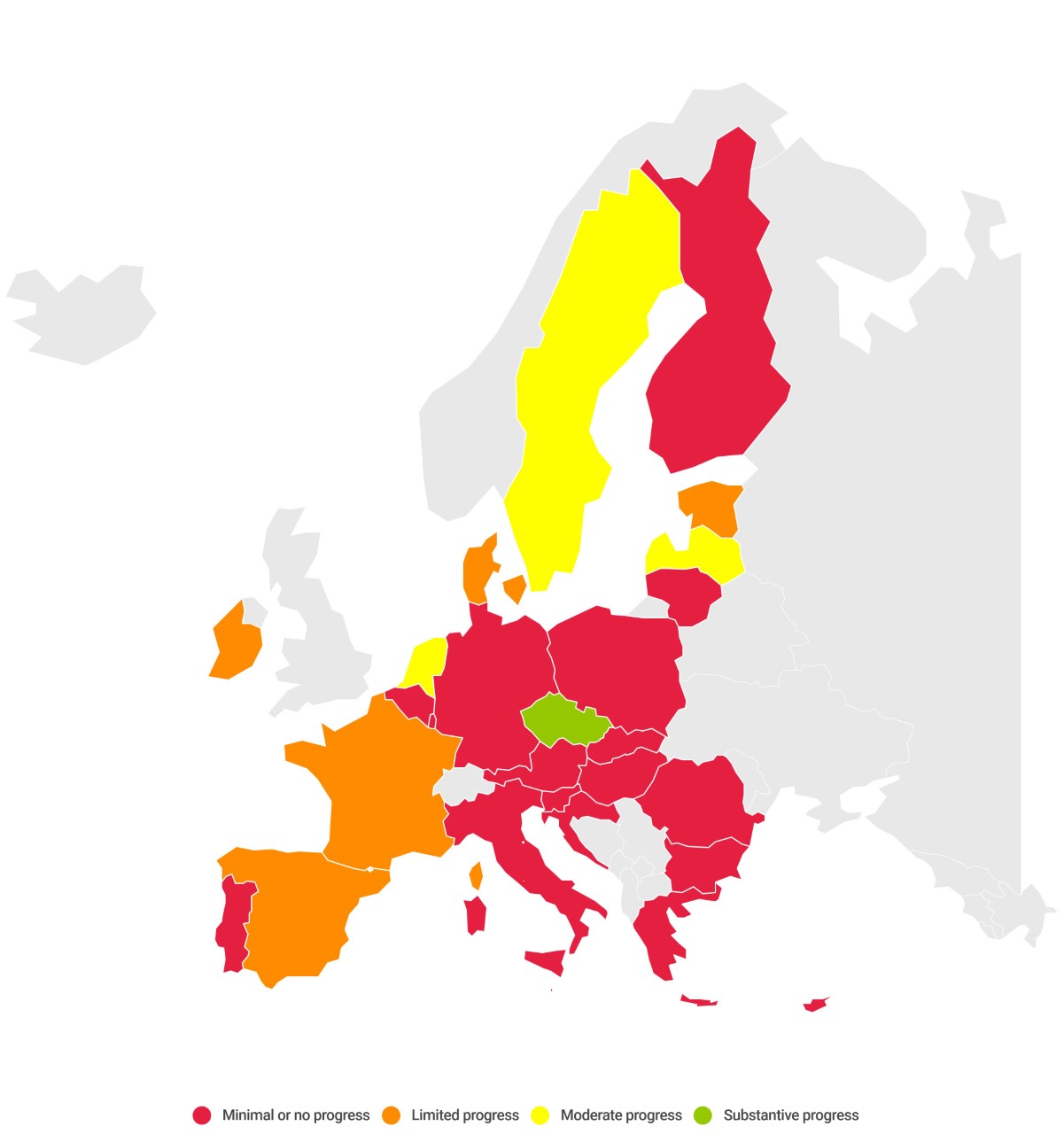

Two new reports on whistleblower protection analysing the implementation of the 2019 EU Directive on Whistleblowing have highlighted the need for legal reforms across the region.

The publications – from anti-corruption NGO Transparency International (TI) and the Central and Eastern European Law Institute (CEELI) provide key analysis on the state of play of EU governments across the 27 EU Member States, which were required to fully transpose the Directive into their national legal systems by the 17 December 2021.

As of today, 7 November 2023 – nearly two years since the deadline - 25 of the 27 EU Member States have adopted transposition laws, with draft proposals still under consideration in Poland and Estonia. Eight Member States have been referred to the European Court of Justice due to their delays and all are facing significant fines. The official mechanism to analyse compliance –– the EU Commission’s Conformity Study - which examines whether Member States’ new laws meet the minimum standard requirements is currently underway.

Visit: EU Whistleblowing Monitor tool - tracking transposition EU Directive on Whistleblowing

Transparency International’s new report ‘How well do EU countries protect Whistleblowers? Mapping the transposition of the EU Whistleblower Protection Directive” - published today - sheds some light on the state of whistleblower protection in 20 of the 27 EU Member States that have adopted legislation. It finds that 19 out of 20 did not meet minimum requirements as they have interpreted them in at least one of the four key areas.

The report reveals significant disparities in the level of safeguards and support provided for whistleblowers and that amendments to the transposition legislation are needed to bring national frameworks in line with the minimum standard requirements of the Directive.

Another report from the Central and Eastern European Law Initiative – also published this week - “Beyond paper rights: Implementing whistleblower protection in Central and Eastern Europe” summarises current progress in six Member States, highlighting the challenges and opportunities of the transposition process as well as making key recommendations.

KEY FINDINGS

The most striking finding of these new reports is that none of the countries’ whistleblowing laws meet best practice requirements. This is despite repeated calls from experts for EU governments to use the transposition process as an opportunity to go beyond minimum standards.

“The EU Directive was motivated by recognition of the importance of whistleblowers to a democratic society, concern about the mistreatment of these courageous truthtellers, and belief that a better paradigm was possible... The EU Directive was an important step, and the largely concluded transposition process was another,” Pender said. “But the European Union, and the six jurisdictions considered in this report, need to continue progressing to ensure whistleblowers are protected and empowered in exposing wrongdoing and can thereby play a vital democratic role.” - Kieran Pender, author of the CEELI Institute Report.

The reports also found:

- Inadequate Scope: Among the 20 countries, only eight protect whistleblowers reporting a broad range of wrongdoings, limiting the scope of protection.

- Lack of Accessible Advice: Three countries do not provide free and easily accessible advice to potential whistleblowers, leaving them without essential guidance.

- Compensation Discrepancy: Only 15 countries offer full compensation to whistleblowers who suffer damage due to their reporting. Additionally, five countries fail to reinstate whistleblowers in their previous positions, leaving them vulnerable.

- Penalties for Violations: Eight countries lack penalties for various violations of whistleblower protection, such as retaliation, vexatious proceedings, interference with whistleblowing, and breach of confidentiality. In contrast, 19 out of 20 countries establish penalties for knowingly reporting false information - with some countries imposing higher penalties on whistleblowers for this reason than against those who violate the protections for whistleblowers. Such high penalties could in fact stop people from blowing the whistle: for example, in France it is criminalised and punishable for up to five years imprisonment.

- Anonymous Reporting: Only 10 countries require competent authorities to accept and follow-up on anonymous reports, while just nine require public and private organisations to do the same.

- Internal Whistleblowing Systems: Only 10 countries mandate all public entities to implement workplace whistleblowing channels for staff, regardless of their size.

- Penalties for Non-compliance: Sixteen countries impose penalties on organisations that fail to implement internal systems in line with legal requirements.

- Legal and Financial Support: Only seven countries' whistleblower protection laws provide for legal or financial support for whistleblowers in legal proceedings.

- Independent whistleblowing authorities: Several Member States now have a dedicated whistleblower protection office, including Slovakia’s UOO and the Huis Voor Klokkenluiders in the Netherlands. These bodies are sharing expertise, challenges and best practices through the new Network of European Integrity and Whistleblowing Authorities which is cause for optimism.

- Potential regression: In countries which had pre-existing whistleblower protections, and despite the inclusion of a “non-regression clause” (Article 25) in the EU Directive, there have been complaints that transposition has restricted rather than strengthened rights – for example in Romania, and Ireland.

- Stakeholder consultation matters: There are examples where governments have not engaged in inclusive or transparent consultation with diverse stakeholders which have resulted in legislative proposals that have caused much concern. For example, in Hungary, an earlier Bill referenced examples of violations of “the Hungarian way of life” such as questioning the “constitutionally recognised role of marriage and family” as within the scope of the law resulting in criticism from the EU and others.

Read more: Hungary has finally started transposing the EU Whistleblower Protection Directive and Can transposing the Whistleblower Protection Directive be done on time? Maybe, but not at the cost of transparency and inclusiveness

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS

Transparency International | CEELI Institute |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CONCLUSION

“Whistleblowers regularly save lives, prevent damages to the environment and help recover millions of euros of much needed public funds that would have been lost to corruption. It is key that policymakers safeguard and empower whistleblowers to come forward to speak up in the public interest” - Marie Terracol, author of the Transparency International Report.

In line with reflections from whistleblowing experts monitoring transposition, these new reports underscore the pressing need for reform of new European whistleblowing laws; to bring protections in line with the Directives own requirements, and international best practice principles for effective whistleblower protection legislation.

A landmark global comparative 2021 study from the International Bar Association looked at whether whistleblowing laws are working, distilling findings into a set of 20 recommended best practice criteria by which to assess the implementation of these whistleblower protection frameworks. By this benchmark, the EU Directive takes joint-first place position, scoring well in 16 out of 20 criteria. This illustrates that EU Member States must take a progressive approach beyond the EU minimum standards to truly reflect best practice standards in whistleblower protection.

An important reminder to all EU Member States is that they are also members of the Council of Europe to whom the Recommendation CM/Rec 2014/7, a legal instrument on whistleblowing applies and which should be considered by these governments when assessing their legislative efforts. Further, the European Court of Human Rights’ jurisprudence on whistleblower protection as part of freedom of expression rights under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights must be taken into account. The landmark Grand Chamber hearing of LuxLeaks whistleblower Raphaël Halet’s case against Luxembourg issued in February 2023 reviews and restates the Court’s criteria for whistleblower protection.

The Whistleblowing International Network joins calls for EU Member States to collaborate with national experts and key stakeholders and start the vital work of reviewing their compliance with the EU Directive and ensuring their laws are implemented in line with international best practice standards.

It is how whistleblowing laws work in practice that matters the most – for society and for the individuals who speak up to protect it!!

NOTES:

The CEELI Institute is an independent, non-profit organisation dedicated to the development and training of a global network of legal and judicial professionals committed to advancing the rule of law. Our efforts are focused on creating independent, transparent, and effective judiciaries, strengthening democratic institutions, fostering efforts to combat corruption, bridging difficult conflicts, promoting human rights, and supporting lawyers and civil society actors in repressive environments. The CEELI Institute is based at the Villa Grébovka, in Prague, a historic nineteenth-century building now renovated into a residence and conference centre.

Transparency International is a global movement with one vision: a world in which government, business, civil society and the daily lives of people are free of corruption. With more than 100 chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, we are leading the fight against corruption to turn this vision into reality.

Written by Balázs M. TÓTH

This article was originally published in English and Hungarian on the ÁTLÁTSZÓ website on the 25 June 2023.

In May 2023, the Hungarian Parliament adopted the Whistleblowing Act, which brings significant changes for those individuals, who wish to report unlawful or corrupt practices of private or public sector organizations.

The adoption of the new legislation was an obligation for Hungary set out in a European Union directive (EU Whistleblowing Directive). However, the transposition of the EU regulation into Hungary’s legal system did not go smoothly. Whistleblowing is closely related to the fight against corruption, yet the European Commission did not include the adoption of this law among the so-called “supermilestones”, which represent the conditions for unlocking the funds froze by the EU. That might be among the reasons why the Hungarian government did not rush with the transposition of the whistleblower protection directive.

Instead of meeting the deadline of 2021, the Hungarian Government submitted the bill earlier this year for the Parliament. While some other EU member states also tried to postpone the harmonization process, none of them displayed this level of disinterest, as the Hungarian legislative bodies in this matter.

During the legislative process, there was a revealing detour that served exclusively the government’s political communication purposes: in the originally submitted bill – deviating significantly from the regulatory concept of the EU directive – there were a set of grounds for reporting named “protecting the Hungarian way of life”, which were included alongside reporting corruption cases.

The Bill, presented by Justice Minister Varga Judit, provided concrete examples to illustrate cases of violation of the “Hungarian way of life,” such as questioning the “constitutionally recognized role of marriage and family” or questioning the “right of children to identify him/herself with their birth gender.”

Unsurprisingly, these parts of the legal text were criticized by the EU, and after a political veto by Hungarian President Katalin Novák, they were ultimately removed from the final version of the law. The apparent intention was to blur the line between corruption cases and the abovementioned identity-driven scenarios, so the government could present itself as a defender of public interest.

The political communication strategy worked, and in the public debate, the focus shifted to the protection of the “Hungarian way of life”, a narrative, that was more favorable to the governing party. This way, the government didn’t have to explain itself for the significantly delayed anticorruption regulations, that should have been adopted a long time ago.

Based on these events, it is indeed difficult to sense the government’s enthusiasm and commitment towards whistleblower protection measures.

Why does whistleblower protection matter?

The Hungarian people’s willingness to report perceived corruption cases is extremely low, and there can be several reasons for this:

- a) Fear of retaliation: whistleblowers may be afraid of facing disadvantages, such as losing their jobs, as a result of reporting corruption or other irregularities.

- b) Perceived ineffectiveness of reporting: some whistleblowers may not believe that there will be any consequences, as they doubt that the authorities will take the necessary actions based on their reports. If they do not believe in that reporting will lead to any meaningful changes, they may question the meaning of taking any risk with reporting illegal actions.

- c) Cultural factors: It may be worth diving into the depths of the Hungarian psyche. Unlike in some other nations, in Hungary, the general opinion suggests, that reporting is morally reprehensible, which view appears in plenty of widely used proverbs as well.

These factors contribute to the reluctance of individuals in Hungary to come forward and report illegal practices.

Despite all of these causes, the Hungarian Prime Minister “promoted” whistleblowing several times during parliamentary debates, and urged those opposition representatives who accused the government with corrupt practices, to report any violations that comes to their knowledge.

Now let’s see how this new piece of law supports our fellow countrymen, who have a developed sense of justice.

How does the new legislation help whistleblowers?

As we stated earlier, it would significantly increase the effectiveness of the fight against corruption, if whistleblowers could be confident, that they won’t face any negative consequences and that their reports could lead to a proper investigation. To address these legitimate needs, the new act orders the affected organizations to adopt the following measures.

a) All private and state-owned companies, with at least 50 employees, along with all state bodies and local governments, are required to establish internal reporting channels. Municipalities with a population below 10,000 are exempted from setting up the system, but entities subject to the anti-money laundering law, such as financial institutions, accountants, auditors, and law firms, are included even if they employ fewer than 50 people.

b) These organizations must designate a person or unit responsible for receiving and handling the whistleblowing reports.

c) Reports can be made either anonymously or indicating the whistleblower’s name. However, if the whistleblower cannot be identified, the affected organisation is not obliged to conduct any investigation unless the report indicates a “fundamental violation of rights or interests.” We believe that this provision weakens the effect of the legislation significantly, as the majority of the whistleblowers will likely prefer anonymous reports, and the law leaves the definition of “fundamental violation of rights or interests” open to interpretation. If the report is deemed to be of public interest (e.g., in the case of suspected corruption), it can also be made through the so-called “protected electronic reporting channel for reports of public interest.” This platform is operated by the Office of the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights, and the Office must ensure that, the organization that is affected by the report does not become aware of the whistleblower’s identity.

d) If the report includes the name of the whistleblower, the reporting channel must ensure, that only authorized persons can access the whistleblower’s personal data. The law also explicitly states that the whistleblower cannot face negative consequences because of their report, particularly naming the termination of employment or reduction of wages. If however such violations do occur, and the employee takes legal actions, it is the employer’s obligation to prove before the court, that the measures were not taken because of the report

e) Organizations must respond to the report within 30 days and obliged to take the necessary actions to handle any unlawful situations. It can involve initiating internal disciplinary procedures, or if the case falls within the jurisdiction of a public body, they should start the proceedings of that organisation.

What can be reported?

The law names two categories:

- Individual complaint: this aims to address violations of rights or interests of an individual, in case the resolution of the reported case does not fall under the jurisdiction of any other public procedure.

- Report of Public Interest: this form of report refers to those cases, that affects the interests of a community or the entire society. Typically, corruption cases fall into this category, making it the more frequently used form of reporting.

So overall: is it a progress or not?

Hungarian NGOs Transparency, K-Monitor, and TASZ already made an assessment when the first version of the bill was published in March 2023. Átlátszó agrees with the main findings of these organizations: based on the final version of the act, it is evident that the government’s aim was to only incorporate the bare minimum required by the EU directive, which cannot be considered too strict in the first place. Moreover, even these minimal measures are being implemented with significant delay. For example, local governments and state bodies received an exemption from the general 2023 deadline, and they only have to set up their reporting channels until 2025.

However, the law can be seen as progress, mainly because a significant number of privately and state-owned organizations will have numerous tasks related to establishing the reporting channels, which will bring this issue into focus, at least during the implementation period. These organizations will be required to develop new internal policies or review old ones, which can contribute to active dialogues within the organizations, which could help alleviate the lack of information and taboos surrounding the topic. However, there is a fear, that most organizations will perceive these legal obligations as an unnecessary burden, resulting in no actual change in the organizations practices, only producing a lot of documents, which don’t have any real-life effects.

After all, the true impact of the new legislation will depend on the potential whistleblowers’ actions. So the key question remains: do citizens trust the state, that it will handle reports according the spirit of the law, and they will be preserved from any negative consequences of reporting?

Visit Hungary’s country page on the EU Whistleblowing Meter here.

By Ida Nowers (Whistleblowing International Network) and Marie Terracol (Transparency International)

19 December 2022

Whistleblowing allows those who witness wrongdoing to bring such issues to light, and is essential to fighting corruption and preserving democracy. Yet across the European Union (EU), laws do far too little to protect those who come forward.

In response, the EU adopted a landmark Directive on Whistleblower Protection in 2019. It included many important provisions to defend whistleblowers across the Union, filling gaps in many countries’ existing legislation and requiring that all member states pass legislation to protect them. Some of the most important include the shielding of whistleblower identities and the obligation for most companies and public institutions to establish whistleblowing mechanisms and follow up on reports. These basic steps are crucial to ensure whistleblowers have the opportunity to safely share the truth and that the reports they bravely make do not go ignored.

Member states dawdling

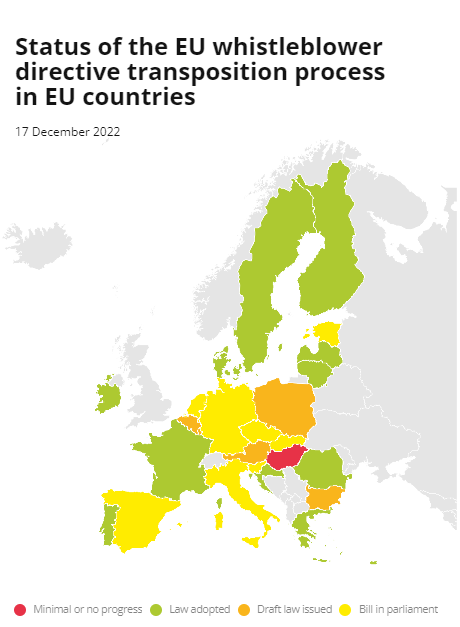

Transparency International and the Whistleblowing International Network (WIN) celebrated the new directive’s adoption and began to track countries’ progress in transposing the law ahead of the deadline in December 2021. In 2019, WIN launched the EU Whistleblowing Monitor, and in March 2021, WIN worked with Transparency International to publish a joint report assessing the transposition process. Yet when the deadline hit, only five member states had adopted relevant legislation. Even more devastatingly, a whole year later, only eight more followed suit – for a total of 13 out of 27 transposing the directive as of now. Thirteen more countries have issued draft laws that will still take time to pass, and Hungary hasn’t even begun the process. Now, we’re left wondering if countries ever intend to take whistleblower protection seriously.

Read more: Map showing status of the EU whistleblower directive transposition process in EU countries

This feeling seems to be shared by the European Commission, which started infringement procedures against EU members states as early as January. In July and September, the Commission took further steps and sent formal requests to 18 countries that had not completed transposition measures to comply with EU law, giving them two months to reply. If their replies are not satisfactory, the Commission may decide to refer these cases to the Court of Justice.

A complicated journey

Just last week, Bulgaria took a big step back when its parliament, in an unprecedented act, rejected the two whistleblower protection bills presented to them. It appears this was due to political manoeuvres rather than the content of the bill itself, in a context of high tension after another failure to form a government. Along with Transparency International Bulgaria, we are urging the prime minister to put whistleblower safety over politics and immediately submit the bill again to the national assembly without revision.

A similar, convoluted, legislative process took place in Romania, where transposition legislation was originally adopted in June and then was quickly sent back to parliament for revision by the president, after concerns were raised about some of its provisions. Thankfully, they didn’t let this stand and a second draft law was presented and finally adopted in December this year.

Content of the law matters

To ensure transposition did not result in weakening existing protection – as eleven EU countries already had dedicated whistleblower protection legislation prior to the adoption of EU-wide rules –the directive did include a non-regression clause. It also clearly stated that governments can go beyond its minimum standards by introducing or retaining provisions that are more favourable to whistleblowers. Governments are thus able to legislate beyond the minimum standards and introduce or retain provisions which are more advanced.

However, significant concerns have already been raised by whistleblower protection advocates that some provisions are potentially regressive.

Experts in Ireland highlighted how the new amendments could directly and indirectly reduce the level of protection already provided, especially the new criminal sanctions for ‘knowingly false reporting’, which could seriously dissuade genuine whistleblowers from considering speaking up. There are similar concerns in Romania that the new law has actually reduced whistleblowers rights by introducing new conditions to report information publicly – limits that did not exist under the previous law.

Even in France, where transposition has been particularly progressive, there are concerns that additional secrecy rules could reduce protection that was available under the previous regime. Absurdly, this would mean whistleblowers in these countries may now be less protected as a result of transposition of the directive than prior to its adoption.

Quality over speed

Governments must act urgently to ensure we aren’t waiting another year for sufficient whistleblowing protections in the EU. Yet they should not use their own past delays to justify working behind closed doors. Lack of transparency and little participation in legislative processes tend to result in ineffective legislation, riddled with loopholes and stymied with practical challenges in implementation, potentially even failing to meet the minimum requirements. This seems to be the case in Portugal, where the new law limits the possibility for whistleblowers to report directly to the authorities, which goes against the directive’s requirement in that regard and is far from best practice. We’re also watching with concern as Italy developed a bill, now before parliament and without proper consultation. In Malta, the law that was adopted seemingly overnight last year is now facing serious criticism and is labelled by whistleblower protection experts a trojan horse.

Only meaningful consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, including practitioners who have experience working with whistleblowers, such as civil society organisations, trade unions, employer associations and journalists' associations – can ensure that the legislation takes into account the challenges and needs of all those most impacted by it, to keep the public safe from harm and corruption.

Whistleblowers across the EU will only feel able to speak up in the public interest if governments properly prioritise the adoption of whistleblowing laws via a transparent and inclusive process. Governments must provide high-level protection, beyond the minimum standards of the directive so that whistleblowers can speak up about wrongdoing that threatens lives, wastes much-needed public funds and puts our entire planet at risk.

Status of the transposition process per EU country on 17 December 2022

In Belgium, the law adopted by parliament on 24 November 2022 only covers the private sector. Another law, for which no draft has been issued yet, is expected for the public sector.

This article was first published by the European Organisation of Military Associations and Trade Unions (EUROMIL).

17 August 2022

Whistleblowers play a democratic role in our society by reporting or disclosing information on a threat or harm to the public interest in the context of their work-based relationship, whether in the public or private sector. Protecting them is a matter of fundamental rights because it is based on freedom of expression and information.

In the military, whisteblower cases in recent years concerned issues of sexual harassment, extreme right behaviour, mistreatment of recruits or misuse of chemical agents. Blowing the whistle in the armed forces is particularly difficult due to restrictions imposed on freedom of expression/speech, professional secrecy and national security concerns. Problems are also linked to internal reporting and the respect of the chain of command. But soldiers should be considered as “workers” and deserve the same level of protection as to any other professional categories. The principle of “Citizens in Uniform” should apply, granting the same rights and obligations to soldiers as to any other citizen. Currently, the protection offered to whistleblowers varies across countries and is fragmented.

In 2019, the European addressed the issue of whistleblower protection and adopted a Directive on the “Protection of persons reporting on breaches of Union law”, commonly known as the “Whistleblower Protection Directive”. On 16 December 2019, the Directive entered into force. From this day, EU Member States have two years to transpose the Directive into their national legislation.

While EUROMIL welcomes the adoption of the Whistleblower Protection Directive, it believes the document contains shortfalls that need to be tackled. The main issue of concern for military personnel is the blanket exception on national security. Another worrying issue is the lack of protection provided to whistleblowers who reveal breaches in the public interest on issues of working conditions, non-discrimination as well as occupational health and safety.

Four months before the end of the two years to transpose the Directive into their national legislation, EUROMIL collected the following information from our colleagues in collaboration with the Gender Equality Secretariat of PFEARFU in Greece.

Greek military personnel may contact the Commander of the Unit personally or create a personal report to initiate a sworn administrative inquiry into the case. In any case (for example, if the sworn administrative inquiry does not succeed) complaints can be made to:

- The Military trade unions – Military personnel may turn to PFEARFU which can offer services including counselling and court action whilst supporting the victim moving forward, so that they are protected;

- The National Ombudsman; and

- The National Transparency Authority – This authority body is responsible for everything concerning the State, including the behaviour of employees, and anyone can file a complaint to the body and on the State website at metoogreece.gr (especially for sexual harassment, abuse, verbal and / or physical violence). However, at the Ministry of National Defence, there is no mechanism for complaints of sexual harassment as such. The new national equality action plan is currently being consulted, including the whistleblowing mechanism of the MoD, where PFEARFU will submit proposals.

As representatives of workers in uniform and based on our experience, we quickly realized that although the classic method of complaints (via hierarchical structures) may seem efficient in some cases, other more complex cases often involve procedures that can become far more time-consuming and lack transparency. In addition, fear of possible disciplinary consequences and social outcry are deterrents to whistleblowers. It goes without saying that the whistleblowers’ identity and the sensitive personal data run the risk of being disclosed. Following on from the above mentioned issues, PFEARFU decided to fill these gaps by creating a communication network through local military associations across the country. Thus, the whistleblowers can turn to competent colleagues outside the camps where the complaints will be managed anonymously and confidentially. Each case is dealt with individually, either with the help of experts (sociologists – psychologists), or through legal means in collaboration with law firms. In particular, with regard to issues of gender equality or equality of opportunity, PFEARFU have set up the military secretariat for gender equality, which aims to:

- Protect military personnel from breaches of the law and regulations concerning gender discrimination;

- Protect human rights and ensure compliance with the principle of equal treatment;

- Highlight and develop solutions for issues, for instance, problems of gender equality with substantiated proposals-suggestions; and

- Organize educational and social events, lectures, seminars etc. in order to inform the military personnel about human rights in the Armed Forces.

PFEARFU’s valuable partners in this context are the National Ombudsman and the National General Secretariat for Gender Equality. The ombudsman has undertaken to monitor and promote the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment for men and women, both in the private and public sectors. On the other hand, the General Secretariat for Gender Equality, in matters of sexual harassment, holds the position of the governmental body regarding the monitoring, planning and implementation of national gender equality policies and the fight against violence against women.

Through a social dialogue with the MoD, MPs, local governments and other related bodies, PFEARFU are currently trying to establish a stable institutional framework by taking advantage of their existing networks, thus making the processes simple, fast, transparent and efficient.

The legal framework used is:

- National law 3896/2010 – Government Gazette 207 / Α / 8-12-2010 which is based on the DIRECTIVE 2006/54/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation;

- National law 4531/2018 – Government Gazette 62 / Α / 5-4-2018 Ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Violence against Women and Domestic Violence and adaptation of Greek legislation (Istanbul Convention);

- Convention 190 adopted by the International Labor Organization (ILO) on the Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the Workplace, which in conjunction with Convention 206 on Violence and Harassment, constitute a framework for action and contribute to the achievement of decent work, which will not include acts of violence and harassment.

PFEARFU are also in contact, and exchange know-how with the Research Centre for Gender Equality (KETHI) which is a Legal Entity of the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (General Government Body) and you can find it in English here.

In summary, EUROMIL would like to emphasize that in the case of Greece, as with a number of other countries, it is clear that the protection of whistleblowers in the Armed Forces is not possible without the assistance of trade unions, which in good cooperation with the MoD, offer realistic solutions that would otherwise be impossible. Confidentiality, anonymity, trustworthiness and personal contact are the cornerstones.

This article was first published on epicenter.works by Petra Schmidt.

26 July 2022

Whistleblowers have an important corrective function in a democratic society because they expose misconduct like corruption, abuses of power and white-collar crimes. They frequently incur high personal risks. Threats directed against them or even family members are however just the tip of the iceberg – dismissals and other consequences that jeopardise their livelihoods are largely the rule in this unequal fight for truth, legality and justice. The cases of Edward Snowden, Frances Haugen, Julian Assange are current examples.

Given the role whistleblowers play in our society, a clear law is required to create straightforward paths for the brave individuals who help expose illegal behaviour in companies and public institutions. The 2019 EU directive on the protection of whistleblowers has created a minimum standard at EU level. But the EU has given member states the opportunity to go beyond this framework – any country could set a gold standard if it wanted to!

The Political Will to Protect Whistleblowers is Lacking

Austria failed to implement the directive in time and consequently risked infringement proceedings.[1] On 3rd June 2022 the draft bill was finally made available for pre-parliamentary expert review, but it closely follows the directive and is anything but a milestone achievement. The proposed whistleblower protection act Hinweisgeber:innenschutzgesetz certainly does not set a gold standard, and it even gives the impression that the exposure of misconduct is not the goal of the Conservative and Green coalition government.

One of our main concerns about the whistleblower protection act is the unnecessary complexity in its scope, which is a source of great legal uncertainty. The scope of the EU directive is already very complicated, and a degree in European law would be helpful in understanding the directive. Unfortunately this was not improved in the national implementation. Beforehand and without legal knowledge it is nearly impossible to tell whether a given revelation will be protected or not. The consequences are clear: Everyone will think very carefully whether they should take the risk of making a report if they might end up unprotected, with a real risk of dismissal and possibly even threats against family members.

Given this state of affairs, the law will probably fail in its actual purpose: Providing individuals with a clear-cut, secure legal space to expose breaches of the law and corruption. The legal framework that has been created offers neither more legal certainty or transparency nor is it more logical. At least there is an option for anonymous reports, and there are provisions for the protection of whistleblowers whose identity becomes known without any action on their part. But on the other hand, an individual on their own will hardly find their way through the maze of rules in this law. Therefore companies with 50 workers or more (the law applies only to them) and public institutions are meant to provide advice themselves. The latter must for instance publish the procedure for filing reports and how this can be done anonymously. So potential whistleblowers should be instructed by potential perpetrators on how to best make their wrongdoings public? This may afford good public-relations opportunities for companies to make themselves look good in the eye of the public. But why did lawmakers miss the opportunity to simply provide clarity themselves, in order to offer a really transparent and protected path for revealing misconduct?

Make Sure Nothing Sees the Light of Day!

To make a report, individuals must in a first step turn to the (internal) reporting office of a company or public institution. Only if this office fails to act is there an option to report to an independent external office. This “independent” external office, however, is none other than the Federal Anti-Corruption Office, which is subordinate to the interior ministry. The deterring effect on whistleblowers will be enormous, given many years of frequent scandals about party-political appointments in the conservative-held interior ministry. We do not understand why the Ombudsman Board (Volksanwaltschaft), which is much more independent and not bound by ministerial instructions, cannot be the point of contact for whistleblowers.

Equally dire is the reporting channel directly to the public and the media: They can only be addressed under very restrictive conditions, which will presumably lead to the loss of valuable support in many cases. In practice, it will probably be safer for many whistleblowers to rely on editorial confidentiality than on this new law.

What is more, the fines that companies have to pay if they try to obstruct whistleblowers, retaliate against them or breach their duty of confidentiality, are a real bargain for large companies. The potential penalty is up to EUR 20,000, and up to EUR 40,000 in repeat cases. No distinction is made between large, financially strong enterprises like Telekom Austria, Strabag or OMV and all the others. For the former, such fines are arguably mere peanuts, and they will probably have little incentive to foster a culture of transparency and openness. Had the lawmakers simply used fines as a percentage of annual turnover as a guideline for companies, like the GDPR does, proportionality and deterrence could have been achieved.

But that is not all: The same potential penalty applies to whistleblowers if they knowingly make false reports. There is no disputing that measures are necessary in such an event. But fines of up to EUR 20,000 are probably not easy to manage for a private individual. Unfortunately, the law fails to differentiate, so that the balance of interests is clearly tipped in favour of financially strong companies.

A Missed Opportunity, Despite EU Requirements

It is really too bad that a courageous and far-reaching implementation of the EU directive apparently is not wanted. The goal of the responsible minister for labour and economic affairs, Martin Kocher, seems not to have been to create a usable and practical instrument for the protection of whistleblowers and to set a gold standard, but rather to bring as few instances of misconduct as possible to the light of day, in the interests of political parties and large corporations. This is a failure and will most likely prolong the present situation, where merely a small share of cases are exposed.

Enlightened, liberal democracies differ from autocratic states in many quantifiable parameters, among them the lowest possible level of corruption. Large companies will be pleased about this law, because thanks to minister Kocher, they will continue to have little to fear from internal whistleblowers. As for the population, the prospects are grim: We continue to be almost unprotected against corruption, and in the end, all of us are paying the price for this backroom deal. In theory this can still change if the green coalition partner or parliament repair the law after their summer recess. We are keeping up the fight!

You can find epicenter.works comprehensive legal statement from the pre-parliamentary expert review here (in German).

Petra Schmidt is the Communications Manager for digital rights NGO epicenter.works.

[1] Der Standard, No whistleblower law: EU initiates infringement proceedings against Austria, Renate Graber, February 10, 2022.

By Ida Nowers WIN’s Law & Policy Coordinator and Dr Simon Gerdemann, a legal scholar on EU law and whistleblowing protection legislation.

20 April 2022

Gerdemann explains the current state of transposition of the EU Directive and some of the key issues for implementation including the "direct effect" of some of its provisions. Gerdemann argues that most Member States have failed to realise that many of the Directive’s provisions entered into force automatically on the 18th December last year. He also explains the need to consider the case law of the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights.

Ida: The EU Directive on Whistleblowing (Dir (EU) 2019/1937) was adopted over two years ago and the official deadline for the 27 member States to transpose it into their national legal systems passed on 17 December 2021. What is the current state of play for transposition?

Simon: Amongst the 27 EU member States, only Denmark and (partially) Sweden adopted new transposition legislation that came into effect before the deadline. Portugal, Lithuania, Malta, Cyprus, Latvia, and France have also passed new laws which will enter into force during 2022.

Read more: List of legislative developments in the transposition

Several other countries have introduced Bills to parliament or issued draft proposals for consultation with stakeholders or the public. Overall, the process however has been delayed and has not been particularly transparent or inclusive.

Read more: Can transposing the Whistleblower Protection Directive be done on time? Maybe, but not at the cost of transparency and inclusiveness

The remaining countries are yet to pass the necessary legal reforms needed to transpose the groundbreaking requirements of the Directive. Four months post deadline, one country remains listed as not having started the process.

Get an update: EU Whistleblowing Monitor list of updates

Due to the Member States’ large-scale failure to transpose the Directive in time, the Commission initiated infringement proceedings in January 2022.

Ida: How would you describe the key mechanisms of the Directive?

Simon: The Directive’s main goal was to improve the effective enforcement of Union law by strengthening the individual protection of whistleblowers and the institutional framework for whistleblowing cases in general. The EU legislator seeks to establish a comprehensive minimum standard in the entire Union, thereby ending the current fragmentation of whistleblowing laws in Europe and the low level of protection in many Member States. To achieve this objective, the Directive relies on four main regulatory elements with various interlocking provisions:

- A comprehensive anti-retaliation law in favour of whistleblowers;

- Obligating organisations both in the private and public sector to set up their own whistleblowing reporting channels as addressees for internal reports;

- Establishing specialised national whistleblowing authorities as addressees for external reporting;

4. Adopting whistleblowing-specific penalties into national law.

Ida: The European Commission described the proposal for the Directive as a “game changer” for whistleblower protection. How does the Directive measure up to whistleblowing legislation in United States and the UK?

Simon: Contrary to what most people would think when they remember cases like that of Edward Snowden and other whistleblowers in the United States, the US can actually be considered the motherland of modern whistleblowing legislation and one of its main driving forces. In some regulatory areas, most notably in the financial services sector, the level of whistleblower protection, incentives and administrative support go significantly beyond even what the Directive now seeks to establish in the European Union. Other whistleblowing laws around the world, and in Europe, also offer quite a robust level of protection at least in some respects, for example the UK’s Public Interest Disclosure Act (PIDA 1998) which was Europe’s first comprehensive whistleblowing law.

Read more: Implementing the EU Directive on Whistleblowing: Lessons learned from UK whistleblowing legislation

That being said, the Directive, while by no means perfect, truly is a game changer. This is especially true for the majority of Member States in the European Union which lacked any kind dedicated, comprehensive whistleblowing legislation.

Yet, even if you compare the Directive’s provisions to existing whistleblowing statutes, the sheer scope of application – especially if Member States choose to extend protection to reports of breaches of national law – is what sets the Directive apart from previous whistleblowing laws. Other countries, like the US, often only protect whistleblowers where the government can use them to compensate for a lack of existing enforcement capabilities - whilst leaving them very vulnerable in other areas of law and practice - resulting in an incoherent patchwork of different levels of protection and procedural requirements.

Read more: Are EU governments taking whistleblower protection seriously? Progress Report on the EU Directive

Since international research and experience has shown that legal certainty is of paramount importance for any effective whistleblowing law, a uniform framework like the one intended by the Directive is truly a significant and indeed an unparalleled step forward.

Read more: Are whistleblowing laws working? IBA GAP 2021 Report

Ida: Given the significant delay of EU countries in adopting the necessary legislation to transpose the Directive – why do you think most countries failed to meet the official deadline?

Simon: It seems that a lack of experience of European policy makers and legislatures with the topic of whistleblowing has likely contributed to delays in many Member States. Until very recently, whistleblowing legislation was relatively unknown to most law makers and legal experts alike. Furthermore, the Directive’s provisions will foreseeably have a very significant impact on existing national laws and legal standards, often completely changing existing national laws and principles, which has led to some intense debate in many Member States.

One major point of contention was, and still is, the question as to whether law makers should extend the scope of application of the law to also cover reports and disclosures of breaches of national law.

Read more: WIN Series: Implementing the EU Directive on Whistleblowing – Whistleblower protection laws must cover breaches of national law

While such a unifying legislative approach, now commonly called “gold plating,” would quite certainly result in a higher level of whistleblower protection, and – consequentially – a higher number of illegal activities being uncovered or public funds being recovered, some political actors argue against this expanded approach. These voices claim that this approach would also bring about significant additional costs for private companies, especially since their internal whistleblowing units would have to deal with increased level of reporting.

Yet, if you look at past experiences of compliance departments, it is quite clear that a uniform standard of whistleblowing rules will by and large not increase the burden due to the amount of reporting, but in fact decrease the burden for implementation costs for private companies and public administrations alike. This is because it would save compliance officials and those otherwise responsible for handling whistleblowers, a lot of time and energy they would otherwise have to spend determining the applicable conflicting EU and/or national legal standards in each individual case.

Read more: 2018 Impact Assessment accompanying the proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of persons reporting on breaches of Union law

Ida: You have described considerable apprehension on the part of policy makers to undertake the required reforms and introduce these mechanisms, are there legal implications for having delayed in doing so?

Simon: There are several legal as well as political consequences that flow from the Member States’ failure to meet the transposition deadline. First of all, the Commission initiated infringement proceedings against 24 of the 27 Member States on 27th January 2022, which may have significant financial and political repercussions depending on how each Member State acts in the future.

More importantly, however, is that most Member States have failed to realise that many of the Directive’s provisions entered into force automatically on the 18th December last year – the day after the transposition deadline expired.

This “direct effect” of the Directive occurs by virtue of principles established by case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). According to these principles, a directive’s provisions automatically enter into force if they impose obligations or detrimental legal effects on the Member State that violated its duty of transposition to the extent that the individual provisions are unconditional and sufficiently precise to be applied directly.

While these principles naturally leave some room for interpretation, it is quite clear that at least the Member States’ obligations to establish internal whistleblowing channels across public administrations, as well as many elements of protection for public sectors whistleblowers, have thus actually come into force already.

This not only allows whistleblower to rely on these provisions regardless of whether a national transposition law exists, but also puts many Member States in a state of constant violation of Union law for as long as they don’t establish functioning whistleblowing units in the administration - which most have failed to do.

Finally, the whole situation is of course significantly detrimental for potential whistleblowers and their need for legal certainty, since Member States inability to meet their obligations under EU law has yet again complicated the current patchwork of different legal rules on whistleblower protection across Europe.

Ida: Given the significant delay of EU countries in adopting the necessary legislation to transpose the Directive – why do you think most countries failed to meet the official deadline?

Simon: It seems that a lack of experience of European policy makers and legislatures with the topic of whistleblowing has likely contributed to delays in many Member States. Until very recently, whistleblowing legislation was relatively unknown to most law makers and legal experts alike. Furthermore, the Directive’s provisions will foreseeably have a very significant impact on existing national laws and legal standards, often completely changing existing national laws and principles, which has led to some intense debate in many Member States.

One major point of contention was, and still is, the question as to whether law makers should extend the scope of application of the law to also cover reports and disclosures of breaches of national law.

Read more: WIN Series: Implementing the EU Directive on Whistleblowing – Whistleblower protection laws must cover breaches of national law

While such a unifying legislative approach, now commonly called “gold plating,” would quite certainly result in a higher level of whistleblower protection, and – consequentially – a higher number of illegal activities being uncovered or public funds being recovered, some political actors argue against this expanded approach. These voices claim that this approach would also bring about significant additional costs for private companies, especially since their internal whistleblowing units would have to deal with increased level of reporting.

Yet, if you look at past experiences of compliance departments, it is quite clear that a uniform standard of whistleblowing rules will by and large not increase the burden due to the amount of reporting, but in fact decrease the burden for implementation costs for private companies and public administrations alike. This is because it would save compliance officials and those otherwise responsible for handling whistleblowers, a lot of time and energy they would otherwise have to spend determining the applicable conflicting EU and/or national legal standards in each individual case.

Read more: 2018 Impact Assessment accompanying the proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the protection of persons reporting on breaches of Union law

Ida: You have described considerable apprehension on the part of policy makers to undertake the required reforms and introduce these mechanisms, are there legal implications for having delayed in doing so?

Simon: There are several legal as well as political consequences that flow from the Member States’ failure to meet the transposition deadline. First of all, the Commission initiated infringement proceedings against 24 of the 27 Member States on 27th January 2022, which may have significant financial and political repercussions depending on how each Member State acts in the future.

More importantly, however, is that most Member States have failed to realise that many of the Directive’s provisions entered into force automatically on the 18th December last year – the day after the transposition deadline expired.

This “direct effect” of the Directive occurs by virtue of principles established by case law of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). According to these principles, a directive’s provisions automatically enter into force if they impose obligations or detrimental legal effects on the Member State that violated its duty of transposition to the extent that the individual provisions are unconditional and sufficiently precise to be applied directly.

While these principles naturally leave some room for interpretation, it is quite clear that at least the Member States’ obligations to establish internal whistleblowing channels across public administrations, as well as many elements of protection for public sectors whistleblowers, have thus actually come into force already.

This not only allows whistleblower to rely on these provisions regardless of whether a national transposition law exists, but also puts many Member States in a state of constant violation of Union law for as long as they don’t establish functioning whistleblowing units in the administration - which most have failed to do.

Finally, the whole situation is of course significantly detrimental for potential whistleblowers and their need for legal certainty, since Member States inability to meet their obligations under EU law has yet again complicated the current patchwork of different legal rules on whistleblower protection across Europe.

Ida: Despite the apprehension of some governments to implement the minimum standard requirements, the Directive includes a ‘more favourable’ clause and civil society, as well as the Commission, has encouraged Member States to go beyond the minimum standards. Some countries, such as France, have taken the opportunity to implement more comprehensive laws which go further than the minimum requirements – what are the benefits of this more progressive approach?

Simon: One fundamental advantage for whistleblowers as well as all other parties concerned in whistleblowing cases is that only comprehensive laws with a broad material scope can truly accomplish the directive’s goal of unifying whistleblowing standards and thus create a level of legal certainty and coherence which the minimum standards alone cannot fully achieve.

Due to the limits of EU competences, the Directive could only cover legal areas which have a direct material connection to matters regulated by EU law, which resulted in a very complex regulatory structure with long annexes detailing in which specific cases whistleblowers would be protected. The Directive itself acknowledges that the current patchwork of insufficient whistleblower protection will only end if the Member States voluntarily expand the scope of the directive by extending it to matters of national law. Some Member States, like for example France and Denmark, have correctly identified these issues and acted accordingly, while others have not.

Beyond that, there are various matters of whistleblowing legislation which the Directive does deal with in detail that would consequentially benefit from well-designed national rules and regulations. One example of this are disclosures in the general public interest, i.e. matters which are of fundamental importance for a democratic society and should thus be discussed in public, like, for example, the issue of mass-surveillance raised in the Snowden case and others. The Directive does not explicitly deal with such matters since its main focus is on improving the effective enforcement of existing EU laws, not on whether current laws and practices actually serve the greater good of society or in fact pose a threat to the public interest or the protection of human rights in the long run.

These and other matters of fundamental importance to democracy are to be decided by the sovereign Member States themselves and should be addressed head-on if a country wants to create a national whistleblowing law that truly serves as a comprehensive framework for all whistleblowing cases.

Read more: The new French whistleblowing law: renewed hope for European whistleblowers?

Ida: You have described how EU directives can have “direct effect” – does that mean EU citizens can rely on the EU Directive directly even if their governments haven’t transposed it into their national legal systems yet?

Simon: To some extent they can, yes. You can think of the European Court of Justice’s (ECJ) direct effects doctrine as something of a punishment for Member States for their failure to transpose a directive in time, which in turn results in legal benefits for that state’s citizens.

From this idea it follows that citizens can generally rely on the provisions of a directive if the other party is the state, which, for example, leads to public servants being able to invoke the rights of the Directive directly after the transposition deadline has expired - in this case starting from 18th December 2021.

Importantly, this principle applies to all state-affiliated entities, no matter if the non-transposition is their fault or not, including, for example, public municipalities. On the other hand, if the other party has no direct affiliation with the state, especially if the employer or contractor is a private company, the direct effects doctrine does not apply. Nonetheless, the Directive can have some effect on private relationships by way of interpreting national laws in accordance with the principles of the Directive, which is another doctrine set up by the ECJ.

Even if we are talking about civil servants or public employees, it is, however, important to keep in mind that only those provisions which are unconditional and sufficiently precise to allow for direct application may be applied directly. According to the ECJ’s case law, this inter alia excludes provisions from direct effects which grant Member States a certain level of discretion when transposing them. This in turn affects whistleblower protection in cases of external reporting to public authorities, which is predicated upon the establishment of a proper whistleblowing authority and therefore most likely can not be invoked so long as a Member State has not yet set up such authorities or not named specific national authorities to be responsible for external reports.

This leaves us with primarily two scenarios in which citizens can directly rely on the Directive’s whistleblower protection provisions:

- First, they can in principle claim protection if they report breaches within the scope of the Directive internally within administrative entities with 50 or more employees and/or civil servants.

- Second, they can get protection under most of the public disclosure provisions, e.g. if they publicly disclose information about breaches which constitute an imminent or manifest danger to the public interest.

In all of these cases, however, one has to keep in mind that the provisions of the Directive and their direct effects are ultimately subject to future interpretation by the ECJ, yet again adding to the legal uncertainty many whistleblowers are still facing in their respective countries.

Ida: It sounds as though only certain provisions of the Directive will therefore have ‘direct effect? What mechanism would you say are enforceable as of 18 December 2021?